|

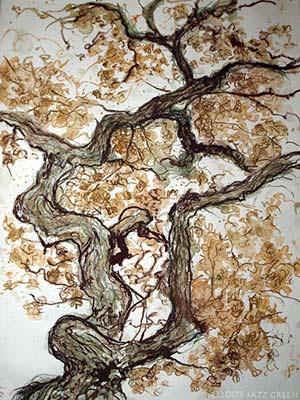

| Bodies on the battlefield at Antietam |

33

The combat man isn’t the same clean-cut lad because you don’t fight a kraut by Marquis of Queensberry rules. You shoot him in the back, you blow him apart with mines, you kill or maim him the quickest and most effective way you can with the least danger to yourself.

Bill Mauldin, Up Front

You know how the boys used to sit all along Brighton front in their blues, an’ jump every time the coal was bein’ delivered to the hotels behind them?

Rudyard Kipling, A Friend of the Family

1974

Death and blood are always there. They are, after all, the purpose of the infantry. That is why we move to and fro upon the earth and up and down in it. To kill. To be killed. To bleed. To die.

Not that I meditated at any length on these ideas. But they struck me at odd times and I sometimes reacted inappropriately.

I went to my war twice. When I returned after the last time I was still a captain. I did not object, because captain was the best rank of all for an infantry officer and it let me stay in the best job of all for an infantry officer, the commander of a rifle company. In this time we were in training. We slipped through the woods and were alert, but not as alert as we would be if our lives were at stake. The alertness was driven as much by the games-like atmosphere as anything else. Some of the sounds were the same — the hissing of the radios, the distant thumping of helicopters, the curses when someone tripped and fell. On the other hand, there was a distance, and not-realness to this game, as if it didn’t matter.

I studied the map. I knew that if I could get my men to a specific location before the Blue Force (my men were the Red Force, the “opposing force,” the enemy), if I positioned my men correctly, if they dug in and performed all the tasks of defense correctly, that the Blue Force would lose. At least that’s the way it was supposed to be. Unless the Blue Force had more people, or they managed to get around a flank, or if they were actually somewhere else. A lot of “ifs.”

This time we did all the right things. We were at the right place. We set up on a very pretty horseshoe-shaped hill with an open field at the bottom of it. My men were there early and we quietly planned our defense and dug in. Listening posts were set up out to our front. We linked up with other infantry companies to our left and right. Through the night we watched and waited and were very silent, very professional.

Not long after dawn the Blue Force battalion came into the field below us. They were in an appropriate formation and they moved reasonably well. They just didn’t know they were moving into a trap. With a few clicks on my radio and a few whispered code words I unleashed my artificial Armageddon. The sounds, although impressive, were not quite right. Belts of blank ammo ran through the machine guns. Blank rifle cartridges banged and flashed in the morning light. A few crashes of artillery simulators and fake hand grenades were heard. Colored clouds from smoke grenades rose up into the air and flowed down the hillside. My heart beat increased. I thrilled to the sounds and sight of destruction.

Then there were whistles and men with white arm bands and soft caps strolled through the smoke waving their arms. These men were not camouflaged and did not carry weapons. They were the umpires, the referees of the game. They called for the commanders of the opposing units.

I came up out of my command post, signaling with my hands for my men to stay hidden. My two radio operators, my RTOs, followed me as always, like remoras constantly circling close to their shark. An umpire who’d been with me in my command post came along, looking clean and unconcerned. We walked down the hill.

My company was quickly judged to have “won.” The Blue battalion was told to withdraw and casualties were assessed. The operation would restart in a couple of hours. I turned and went back up the hill, calling in a situation report as I went. My platoon leaders and their sergeants were waiting for me.

“We won,” I told them. “Decisively. They’re assessed thirty percent casualties and have been told to move back 3 klicks to refit.” The lieutenants grinned and left to inform their men. Their sergeants just nodded and followed them.

The news rippled along the line from foxhole to foxhole.

“Teach them assholes to take on the Cold Steel Cobras.”

Calls flowed down the slope toward the Blue Force soldiers.

“Come back another day, pussies!”

“Call yourselves soldiers? We saw your butts coming a mile away.”

And more friendly curses and belligerent shouts.

Behind me I heard the sound of a jeep bringing up supplies. In the distance I could hear the thumping of a helicopter, probably one of the bosses circling around. Below me, down in the bowl into which they’d come, the Blue battalion was gathering itself. Some of the men stood up and drank from their canteens. A medic was working on the leg of one of them, probably a twisted ankle. Their battalion commander was arguing with the umpires about something. A slight breeze blew the smell of smoke up the hill.

And then it was as if a cloud had passed in front of the sun. The golden grass below me seemed to fade and flicker. The image shifted to one that looked like a civil war photograph. The color leached out of the ground and every shadow was a pool of blood, every manshape was dead or dying. The bodies were everywhere, bodies and pieces of bodies and metallic debris. A grimacing head lay at the foot of the slope. Churned dirt and shattered tree stumps marked the impact of artillery shells. The faint sounds I heard were the calls of the wounded. Thin wisps of smoke rose everywhere across the valley floor and what movement I saw was like the movement of crippled insects lurching away from the light into the far darkness. The thrilling, atavistic surge, my soaring sense of triumph abruptly spiraled downward. Victory spilled out of me like vomit splashed to the ground.

I heard my troops begin one of their marching songs, a song filled with jokes and obscene affirmations of their prowess as soldiers and men. It was a song I’d heard and smiled at a dozen times, but now it infuriated me, filled me with an unresolved, unreasoning rage. From deep in my belly came the voice I used on parade grounds, the voice that could echo across a hundred yards and still a thousand marching soldiers.

“At ease!” I barked.

The command blew across the hill and the hill was still.

More quietly, almost to myself, I muttered, “Every one of those sonsabitches is dead. It is not their fault, God damn them!”

I could say no more.

My cluster of RTOs and the artillery forward observer, my personal little command group, drifted away from me. In the valley below an umpire wearing a soft cap and white arm band looked up at me. All of the Blue Force had heard my order and they, too, were silent. An empty circle was around me, a bubble that no one would breach, no one could understand. I turned to look down the hill again and took my helmet off.

Behind me I heard one of my RTOs mutter, “What the fuck got into him?”

“Beats the shit outa me. But I’m not gonna ask.”

My First Sergeant strode through the cluster of men and into the silence. He walked swiftly up to me and stopped directly in front of me in a rigid posture of attention. His dark, almost black eyes stared out from under his helmet. He looked directly into my eyes. I’m sure he saw the rapid breathing, the color of my face, maybe a muscle jumping on the side of my jaw. When he spoke he was very formal and it reminded me that he, the First Sergeant, was also an infantryman, that he had been an infantryman for a very long time. He was in full field gear that hung from his shoulders and around his waist as if he’d been wearing it all his life.

“Sir,” the First Sergeant said in a still, quiet voice pitched so low that only I could hear him, “Battalion has ordered us to ‘go admin’ and redeploy. They’ve designated a PZ about a klick from here.”

He held up a plastic-covered map and showed me where he’d drawn a circle on it. “With the Captain’s permission, I think it would be good training for the junior NCOs to take charge and run the extraction and insertion.”

My heart was still racing. I was barely seeing the First Sergeant. What I was seeing was the dead, the hundreds of dead. I blinked and gave a short nod.

The First Sergeant spun around and pointed at one of the RTOs. His voice lashed out at him. “Soldier, the Captain wants all the platoon sergeants and the lieutenants here. On me. Right now!”

“Yes, First Sergeant,” the RTO answered and he began talking into the handset of his radio.

In a moment helmeted heads were bobbing along the crest of the hill. The First Sergeant walked about ten meters away from me. The sergeants and lieutenants formed a small circle around him. He showed them the map.

“Put your next senior NCO in charge of your platoons and tell me who it’s going to be. We’re moving out. March order third platoon, second platoon, first platoon. Third platoon, you secure the PZ. We’ve got three flights of six coming in forty-five minutes. Set it up. The Captain has put me and the junior NCOs in charge of the operation. Platoon sergeants, the Captain wants you to get down there and tell those dumb assholes how they got all their men killed. Lieutenants, sirs, I suggest you do the same.”

He turned to the forward observer. “You. The Captain would like you to go with the lieutenants and help them explain to the Blue Force just how fucked up they were.”

He turned back to the sergeants. “Just make sure that they know it was the Cold Steel Cobras that whipped that entire battalion’s ass. And that we could do it again. Any time. Any place. But that they made it easy for us today. Any questions?”

There were none. The platoon sergeants murmured into their radios as they went down the slope and other helmeted heads came bobbing over the hill towards the First Sergeant. The First Sergeant pointed at one of the RTOs.

“There’s a thermos with coffee in it in my jeep. Get the Captain a cup.”

The soldier scurried off.

Down the slope I saw the Blue battalion commander still arguing with the umpires. Their words didn’t carry up the hill, but the lieutenant colonel was waving his arms at them. The Blue battalion’s command sergeant major was back near that commander’s little cluster of radio men. One of my platoon sergeants went up to the sergeant major. I saw them standing side by side while my platoon sergeant spoke rapidly and pointed me out on the hillside. The sergeant major nodded once and then walked over to his battalion commander and took him off to one side.

I was handed a canteen cup filled with coffee. The hot metal burned my lips as I took a sip, but it didn’t matter. I was still staring at the field below me, at the dead men now walking and talking. I should not be proud of this, but I was.

“Nice day,” my First Sergeant said as he came up and stood alongside me and offered me a cigarette.

I looked at him, as if seeing him for the first time. “Good to see you, Top. You came up with supplies?”

“Yes, sir,” he said as he lit a cigarette of his own. “Looks like we figured this one out right. Men did a good job.”

“Yeah, we did.” I gestured down the hill to where the defeated unit was moving out and the landscape was turning back to normal. “They didn’t. We woulda slaughtered them. Just goddamned wiped them out. No goddamned excuse for that.”

“No, sir. I take it the Captain’s pissed off because the Blue force is no good, sir?”

My mood shifted as suddenly as it had come on me, as if the cloud blocking the sun had drifted on through the sky. I came back to the game. I smiled. “That’s right, Top, I’m pissed at them, not us. We did fine.”

The First Sergeant field-stripped his cigarette and put the filter in his pocket. “Company’s ready to move. Let’s walk with ’em, sir. The platoon sergeants will make sure the lieutenants find us.” The First Sergeant had nothing but contempt for lieutenants. In fact, he talked to them only when he absolutely had to.

“Right, Top. Let’s go. Thanks for setting it up.”

I field-stripped my cigarette and we walked off together towards the Third Platoon. The First Sergeant shouted, “Move out!” and the platoons shook themselves into formation. The RTOs were circling within calling distance of me. I threw the dregs of the coffee out of my cup and tossed the cup back to the RTO.

It was not yet noon on this fine Kentucky morning and I noticed an immense dogwood tree in full bloom. Spring was close at hand.

“We really did kick their ass, didn’t we, Top?”

“Yes, sir.”

“This is one hell of a company, isn’t it?”

“Yes, sir. Proud to be in it.”

“So am I, Top, so am I.”

It was a good day. The men began to sing again and I saw out the corner of my eye the gesture from the First Sergeant that signaled that it was OK.

And so the soldiers moved through the Kentucky morning, blood on their hands, a song on their lips, proud, happy, moving to and fro upon the earth and satisfied with doing just that and only that.