|

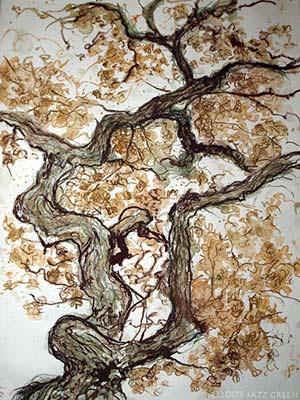

| Jump in Tonight, Torrijos Airport, by Al Sprague, 1990 |

26

Stand up! Hook up! Shuffle to the door,

Jump right out and count to four.

If that chute don’t open wide

Meet your maker on the other side.

Marching song, U.S. Airborne Infantry

Almighty God, we kneel to Thee and ask to be the instrument of thy fury in smiting the evil forces that have visited death, misery, and debasement on the people of the earth....Be with us, God, when we leap from our planes into the dark abyss and descend in parachutes into the midst of enemy fire. Give us iron will and stark courage as we spring from the harnesses of our parachutes to seize arms for battle. The legions of evil are many, Father; grace our arms to meet and defeat them in Thy name and in the name of the freedom and dignity of man....Let our enemies who have lived by the sword turn from their violence lest they perish by the sword. Help us to serve Thee gallantly and to be humble in victory.

WW II Regimental Prayer

506th Parachute Infantry Regiment

1967

Nothing is more terrifying to an infantryman than being alone. An infantryman is part of a collective that sustains him, shapes him, and protects him from at least some of the chaos around him. The collective will, briefly, grieve for him.

I rode through the sky over North Carolina in a C-130. I was part of an infantry company organized into ten-man “sticks” and belted into seats that ran along the outside of the cabin and in two long rows down the center. Overhead, metal cables were stretched the length of the aircraft. I was at the end of the first stick, the one nearest the right-side door. Outside, down below me, pine trees stretched up into the sky, open pastures of fescue and small plots of tobacco were growing. It was early in the year and dogwoods were in bloom. But I couldn’t see any of it because the C-130 had only a few windows and I wasn’t near one of them.

Like all the rest, I was thoroughly trussed up in a parachute harness that bound me through my crotch. I had to carefully arrange my testicles before I moved anywhere. The big main parachute on my back cushioned me, but also pushed me forward in my seat so that I was sitting on the hard edge. A line came over my shoulder from the main parachute and ended in a metal snap link temporarily attached to my harness. This was the static line. Clipped and tied to the front of the harness was another parachute. Also strapped to the harness was an equipment bag filled with gear — ammo, clothing, food, water, entrenching tool, the odd necessities of war. Laced to a leg was a scabbard holding an M-16 rifle. I was wearing a heavy helmet with its chin strap tightened.

We were so immobilized that many of the soldiers simply relaxed, hung in their harnesses, and slept. One yawned, a typical stress reaction. One after another copied him. Down the row men stretched their mouths, exposed their teeth, and filled their lungs with air. Those who smoked wanted to have a cigarette, but that was out of the question. Almost all of them really wanted to take a piss.

On a signal I couldn’t hear over the roar of the engines, the Air Force crewmen opened the doors on both sides of the plane. The noise of the engines jumped higher and howling wind blasted into the cabin. Sergeants wearing goggles and tethered to the frame of the aircraft, the jumpmasters, began peering out of the doors.

Finally the ritual began. The ritual had been so rigorously rehearsed that every man in the aircraft would do exactly as he should, exactly when he should, and whatever he might feel simply would not be felt. Each command — “Get Ready!” “Stand Up!” “Hook Up!” “Check Equipment!” — was done exactly so, because it must be done exactly so.

I was watching the jumpmaster standing in the buffeting wind of the open door. I (as everyone else) was waiting for the command to “Get Ready!” When it came I freed my seat belt. Then with my right hand I gripped the snap link attached to the static line hanging across my shoulder.

I didn’t hear the jumpmaster scream, “Stand Up!” But I could see him sweep his arms upward in the signal and I knew what was coming anyway. The two outside rows of trussed-up men struggled out of their seats and formed bulky, hump-backed lines down the aisles of the aircraft’s cabin.

At the signal of “Hook Up!” I grabbed the cable running overhead and attached the snap link with the static line to it, giving it a hard pull. The static line was, curiously, a lifeline. If the line did not rip open the pack on my back then I would simply fall to the earth, down into the trees, the tobacco plants, the cloud-like blooms of the dogwoods.

At “Check Equipment!” I looked carefully at the gear of the man in front of me, testing the connections, making sure it was perfect. Facing the door, I whacked the butt of the man in front of me to signal OK.

At “Stand in the Door!” the first man in the stick did just that. He shuffled up to the open door. One hand held the static line that been hooked to the steel cable overhead, the other hand slapped the near side of the door frame. He handed his static line to the jumpmaster and turned to look out into the sky beyond the door. He slapped the far side of the door frame with his left hand and stood there, face to the horizon, hands on the frame, feet on the edge of the door, rigid, knees bent, like Samson in the Temple, listening to the howling wind and engines, waiting for the jumpmaster’s signal.

The rest of our stick shuffled forward, reserve parachutes pressed against the main parachutes. Since I was the last man in the stick, I pushed forward as hard as I could until the stick was collapsed like an accordion that has wheezed out its last reedy note. When the jumpmaster screamed “Go!” we would all pour out of the door. It was inevitable. It was pure ritualized collective action. It was part of my job to make sure that they all must go. There would be no jump refusals in this stick.

The jumpmaster screamed “Go!” and hit the man in the door on his butt, hard, and the first man’s legs pushed him forward. He disappeared into the wind and noise. The shuffling men surged forward into the hole he left. The steel cable rang with the sound of sliding snap links. Each man briefly paused then vanished into the roar.

As I neared the door I remembered our training insisted that each man was to stop at the door and strike the same rigid pose as the first man: head up, hands on both sides of the door frame, knees slightly bent. But the wind was rushing past and it was not like when I rode through the summer nights with my grandfather. When I opened my window and held my hand in the wind, feeling my hand dance in the air. This was a storm of air that would rip my arm from my body if I gave it a chance. None in the stick waited for the slap on the ass and the shouted “Go!” The line behind him was pushing too hard. Each must go!

So, as soon as I reached the door, I left.

As the wind plucked me from the side of the aircraft, I tucked myself tightly into a stiff folded shape, my arms across my reserve parachute in front of me, my elbows in, my feet and knees together, my chin down. At that moment I became totally, absolutely, utterly alone. My group of men became a scattering across the sky.

The ritual demanded a screaming count — “One Thousand! Two Thousand! Three Thousand! Four Thousand!” Just between “Three!” and “Four!” a giant hand reached out and snatched me back up into the sky. I was suddenly hanging, swinging in the air.

From the ground it would have looked as if olive green blossoms were opening up against the blue.

The ritual continued. My hands reached up to find the risers. I checked my canopy looking for holes where a line might have snapped over and melted the nylon. I looked for lines that might have looped over the top to create the bulges called a Mae West. I looked for an entanglement where the canopy had not opened at all. When my check of my canopy was complete, I looked around for other canopies beside me, above me, below me.

Finally I looked to the ground below my feet. If I looked closely I could see it moving past. The movement gave me a reference point for the wind. I got ready to drop the bundle of equipment tied to me so that it would hang from a line below me, drift with me, and hit the ground before me.

On a good day there was a moment when I was free and alone as I rode in the air. A good day was when the harness was not crushing one of my balls back up into my groin, when the snap of the opening didn’t wrench the muscles of my neck and create a fierce, lingering ache, when some asshole wasn’t walking across the top of my canopy or drifting into me across the wind, or when it wasn’t so damn cold that I couldn’t feel my fingers, or when the wind wasn’t pushing me so quickly across the ground that I just knew I was going to crash and burn. A good day was when I was up there with the birds, drifting through the air with them, when I could see almost forever across a green horizon.

And then I remembered that I was alone. I must not be alone. If I am alone then I am lost.

The stick was strung out in the sky in a line, the wind line, the first man lowest, the last man highest. Even in the air they were trying to get back together. The first man turned his ’chute and tried to run against the wind and shorten the line. As the last man I tried to run forward to the front. Ultimately, however, where we would land was predetermined by the pilot, the direction he was flying, the altitude of the plane, and by the force of the wind. I had little more control over my destiny than that of a cigarette flipped out of the window of a speeding truck.

Eventually the ground below me took form. What was a pebbled texture became individual trees. The open field of the drop zone appeared free of rocks or other hazards. I tried to relax. I released my equipment bundle to hang below my feet. I turned my canopy to face into the wind. At the last moment I put my feet together and looked toward the trees on the horizon. I did not want to be looking at the ground because I knew the rush of it would make me flinch. I wanted it to be a surprise and it was. The landing was a rushing, bumping sensation, like being tackled. To my body it was just another ritual. I’d done it thousands of times off platforms, tens of times like this, for real. My body did what it had to do. I was compelled into a rolling landing by the wind that still filled my canopy. I came to my feet and jogged with the wind, around the canopy, and the canopy collapsed.

It was over. I was on the earth. All that mattered to me now was finding everyone else, for they were my life. My head turned and turned as I disconnected my harness, as I rolled up the ’chute and stuffed it into the bag I carried with me, as I knelt and checked my rifle. I must join up with my stick, my squad, my platoon. I saw a few figures on the edge of the drop zone. I moved in a shuffling run toward them. We gathered there in ones and twos, threes and fours. Again and again the names were checked until we knew we were all accounted for. We formed a loose circle, facing outward, like a herd of wild animals protecting their young. But we were protecting ourselves.

I was nothing there. We were everything. By myself on the ground I was vulnerable, in control of nothing. We were a team. We must establish our control over a piece of dirt right now. If not where we stood, then someplace we could get to as quickly as possible. If we must move, we must do it now and we must do it together. We desperately searched for the landmarks, the assembly areas, the real places that were marked on maps or photographs.

In my rational mind I believed that it didn’t work very well, this jumping out of airplanes. That is, it didn’t work very well as a tactic for winning battles. Yet no one doubted that the units that jumped out of airplanes were the elite of the infantry. It had everything to do with being alone that moment in the sky, with being scattered like dandelion fluff in the wind, and with that fear-filled aloneness being followed by a coming together, a finding of each other or being found. When two got together, then three, then five, the collective could face a threat together. That lonely moment in the sky created a need, then built a bond among those who did it and then came together.

It was an exclusive grouping in peace or battle. Fitness was everything. Injured men were recovered and remained a part of the group until they overcame their injuries, or were evacuated, or died.

Ritual provided for the dead and wounded. It enclosed them. Ceremony excised them from the body of the unit like a surgeon’s scalpel. The lost were remembered coldly, ritualistically, symbolically, but outside the living body of the unit.

Peacetime: “Yeah, he augured right in. Main malfunctioned. Reserve wrapped around the main. What a mess.”

Wartime: “Couldn’t get a medevac in. We humped that sonofabitch five clicks before we could get to a LZ. Good man. Gonna miss ’im.”

Part of the trick of getting men to die is putting them into units, into teams, because the unit is immortal. So maybe they will be, too. Even if they die keeping the rest of the unit alive.